Physical distance matters when it comes to educational equality. Long commutes to upper secondary schools limit the educational opportunities of young people living in rural areas.

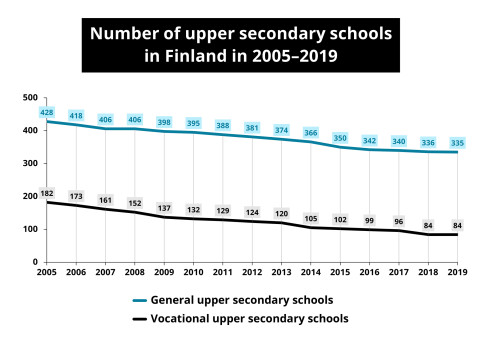

In the mid-2000s, Finland had a network of 428 general upper secondary schools and 182 vocational ones. Over the past 15 years, this network has been heavily reduced: almost every fourth general upper secondary school has been closed down, and the same is true for more than half of the vocational ones. An increasing number of young people finishing their comprehensive school in a rural area now face a situation where their nearest upper secondary school is dozens of kilometres away.

A survey published by the Regional State Administrative Agency in 2016 shows that there is also great regional variation in access to upper secondary education, with Eastern Finland and Lapland facing the grimmest situation. According to studies completed at the University of Eastern Finland, long distances to schools limit young people’s opportunity of choice and make their school days heavier. In addition, their choices are more closely tied to the financial resources of their parents, and to how their parents feel about the role of education.

“The Finnish discourse on schools still starts from the assumption that young people live in urban areas, with schools located nearby,” Researcher Mari Käyhkö says.

This is not how it should be, since the urban-centric discourse on educational equality ignores greater regional polarisation. Over the past five years, Käyhkö and her colleagues, Researcher Päivi Armila and PhD Student Ville Pöysä, have been following up on the lives and educational choices of 16 young people born in 2000 and living in rural and sparsely populated areas. The follow-up study constitutes part of the Youth in Time study.

“We found that young people who live in rural areas and commute to their upper secondary school don’t have time for hobbies or other leisure time activities. They wake up at five in the morning and are back home at four or six in the evening, sometimes as late as at eight. On school days, that is what their everyday life is like,” Armila says.

Where you live limits your educational choices

Many small upper secondary schools are among those that have been closed down. The Finnish educational map now shows an increasing number of municipalities without any upper secondary schools at all. The Regional State Administrative Agency's survey also shows that in 2016, Finland had 35 municipalities where 16-year-olds had a one-way commute of more than ten kilometres to their general upper secondary school. In upper secondary vocational education, the situation is even worse: in 106 municipalities, students’ commute to their nearest upper secondary vocational school is at least ten kilometres.

“Young people are expected to get an education. At the same time, schools taken away from within their physical reach, and this creates educational vacuums. In this discourse, problems get pinned on the individual,” Käyhkö points out.

Besides having a longer commute to school, young people living in the remotest municipalities of Eastern and Northern Finland also have less educational opportunities to choose from. In vocational education, for example, the number of programmes is limited and they are not offered in fields preferred by young people.

Young people are expected to get an education. At the same time, schools taken away from within their physical reach, and this creates educational vacuums.

Mari Käyhkö

Researcher

“The right of every young person to pursue their dream and to make choices that support that dream is acknowledged in strategies of education policy,” Armila says.

For many, this means moving to a city and closer to better educational opportunities. These choices, in turn, are determined by the family’s financial situation and living-related arrangements, among other things.

“Young people finishing their comprehensive school are still tied to their parents and can’t make fully independent decisions on where they wish to live. Families have to think about whether to let their child move to another city, and whether the child wants to move in the first place,” Käyhkö says.

Many of the young people in the study had to live at home and commute to school simply because their family couldn’t afford any other solution. Often, this meant a long commute.

The right of every young person to pursue their dream and to make choices that support that dream.

Päivi Armila

Researcher

Girls in particular feel the pull of urban society that values education. They move to cities in pursuit of better educational and career opportunities.

“Girls grow, and are being raised, into this thinking,” Päivi Armila says.

Those choosing to remain in rural areas are often young men. Ville Pöysä is currently writing a PhD thesis where he examines young men’s relationships to their villages. These young men are not some sad cases still living with their parents; instead they have jobs and meaningful things to do in their sparsely populated village.

“They also have friends and a social life where they live, and they are not lonely. They’re just on the sidelines when it comes to the career-centred thinking of our society that values education,” Pöysä says.

Gendered opportunities and cultural expectations are one explanation for why young women leave rural areas and young men stay behind.

“Rural labour markets are more masculine, and urban labour markets more feminine,” Mari Käyhkö says.

Finland needs new type of pedagogy that addresses students living in dorms

Many of the young people in the study chose to move to a city and to live in a student dorm. Often, however, they were not seen as safe nor comfortable. Young people also needed space and privacy, which is something today’s dorm rooms fail to provide.

Indeed, the researchers call for pedagogy that would address students living in dorms, offering them a safe and home-like environment.

“The fact that a dorm has video surveillance doesn’t make it a safe or home-like environment for a 15-year-old to live in. Living in a dorm should be looked at from a broader perspective that would also take emotional aspects into consideration,” Armila points out.

Young men have found jobs and meaningful things to do in their sparsely populated villages.

Ville Pöysä

PhD Student

Young people are not interested in distance learning

Last spring, the coronavirus pandemic forced Finnish schools to take a digital leap. All talk about distance learning soon became a reality in basic and upper secondary education alike. But could distance learning be a sustainable solution for young people in rural areas in terms of general and vocational upper secondary education?

“For young people, schools are important platforms for social interaction. They are not interested in distance learning: this has been studied exhaustively,” Käyhkö says.

She also points out that distance learning can increase educational inequalities among children and young people. The role of family background gets emphasised in distance learning, especially among younger children. Not all parents have the time or the resources to be actively involved in their children’s distance learning.

“A good thing is that distance learning during the coronavirus pandemic has made the various social roles of school visible. School meals are one example.

Young people living in rural areas often have to make compromises in their everyday life when they start in an upper secondary school. This is something that should be acknowledged also in education policy discourse.

“People have always moved away from rural areas, and this is also something young people have grown to accept. But is it fair? That's a whole another question,” Armila says.

Top photo: Research shows that the time spent commuting gives an opportunity to rest or to do other things there isn’t otherwise time for.