High fat mass in adolescence causes insulin resistance, which can lead to a vicious cycle of worsening insulin resistance and obesity by young adulthood, a new study shows. However, having a high muscle mass partially protects against insulin resistance.

The study was conducted in collaboration between the Université de Montréal in Canada, the University of Bern in Switzerland, Aarhus University in Denmark, the University of Bristol in the UK, the University of Exeter in the UK, and the University of Eastern Finland, and the results were published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Childhood and adolescent obesity remains a global epidemic. Estimated by body mass index (BMI), obesity has been associated with several cardiovascular, neurological, and musculoskeletal diseases as well as type 2 diabetes in adulthood. However, BMI is a poor measure of obesity in childhood and adolescence since it does not distinguish between muscle mass and fat mass.

Insulin resistance occurs when cells in the body fail to take up glucose from the blood in spite of a normal amount of insulin production, leading to overproduction of insulin, known as hyperinsulinemia. Insulin resistance is a precursor of type 2 diabetes already in youth, but long-term studies relating to the association of total body fat mass, abdominal fat, and muscle mass with the risk of insulin resistance in a large population of young people are lacking.

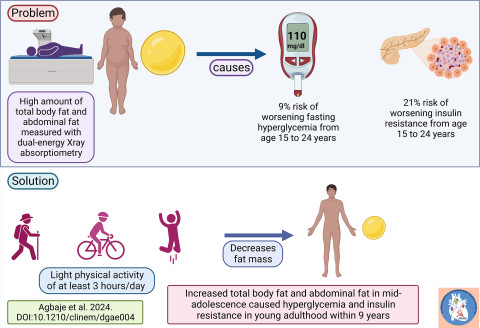

The current study used data from the University of Bristol’s Children of the 90’s cohort, also known as the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Altogether 3,160 adolescents, 1,546 males and 1,614 females, were included in the analyses. The adolescents were 15 years old at baseline, and they were followed up for 9 years until young adulthood at age 24 years. Total body fat mass, abdominal fat, and muscle mass were measured with dual-energy Xray absorptiometry at age 15 years, and repeated at age 17 and 24 years. Similarly, fasting glucose and insulin were measured from blood samples taken at ages 15, 17, and 24 years, and insulin resistance was calculated.

With extensive control for inflammation, lipids, blood pressure, smoking status, sedentary time, physical activity, socio-economic status, and family history of cardiovascular disease, it was observed that each 1 kg cumulative increase in total body fat mass from mid-adolescence through young adulthood increased the risk of excessive blood glucose (hyperglycemia) by 4%, abnormally high insulin level (hyperinsulinemia) by 9%, and insulin resistance by 12%.

Each 1 kg increase in abdominal fat had even more pronounced effects, increasing the risk of hyperglycemia by 7%, hyperinsulinemia by 13%, and insulin resistance by 21%. However, each 1 kg increase in muscle mass reduced the risk of both hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance by 2%.

It was also found that a high amount of total body fat mass at age 15 years caused high insulin resistance at age 17 years. A high amount of body fat mass at age 17 years caused high insulin resistance at age 24 years, and, simultaneously, high insulin resistance at age 17 years caused high total body fat mass at age 24 years, resulting in a vicious cycle. The results were consistent in both males and females, regardless of BMI.

“This is the first long-term evidence of the morbid danger of high total body and abdominal fat in the young population, with abdominal fat twice as dangerous as total body fat. To observe a vicious cycle of fat mass and insulin resistance between the ages of 17 and 24 years is extremely disheartening. Fat mass contributes 75%, while insulin resistance contributes 25% to the fat mass-insulin resistance vicious cycle. Therefore, preventing weight gain is the best way to break this cycle,” says Andrew Agbaje, an award-winning physician and paediatric clinical epidemiologist at the University of Eastern Finland.

“Nonetheless, there is good news: we recently established that sedentary time contributes 10% to the total body fat mass gained in youth years, which can be completely reversed by 3-4 hours/day of light physical activity. Although the increase in muscle mass lowers insulin resistance only by a small amount, its protective effect when combined with light exercise may be critical to reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes. This is why teenagers should be encouraged to take up light physical activity as discussed in a recent podcast,” Agbaje continues.

Dr Agbaje’s research group (urFIT-child) is supported by research grants from Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation, the Finnish Cultural Foundation Central Fund, the Finnish Cultural Foundation North Savo Regional Fund, the Orion Research Foundation, the Aarne Koskelo Foundation, the Antti and Tyyne Soininen Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation, the Paavo Nurmi Foundation, the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, Ida Montin Foundation, Kuopio University Foundation, the Foundation for Pediatric Research, and Alfred Kordelin Foundation.

For further information, please contact:

Andrew Agbaje, MD, MPH, FESC, Cert. Clinical Research (Harvard), Principal Investigator (urFIT-child). Institute of Public Health and Clinical Nutrition, School of Medicine, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland. andrew.agbaje(a)uef.fi, +358 46 896 5633

Honorary Research Fellow – Children's Health and Exercise Research Centre, Public Health and Sports Sciences Department, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK. a.agbaje(a)exeter.ac.uk

https://uefconnect.uef.fi/en/person/andrew.agbaje/

Link to the article:

Agbaje AO, Saner C, Zhang J, Henderson M, Tuomainen TP. DEXA-based Fat Mass with the Risk of Worsening Insulin Resistance in Adolescents: A 9-Year Temporal and Mediation Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024 Jan 4:dgae004. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgae004

Listen to Dr. Agbaje’s podcast interview:

About Children of the 90s

Based at the University of Bristol, Children of the 90s, also known as the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), is a long-term health research project that enrolled more than 14,000 pregnant women in 1991 and 1992. It has been following the health and development of the parents, their children and now their grandchildren in detail ever since. It receives core funding from the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust and the University of Bristol.