The debate around food and nutrition is often characterised by a weight-oriented mindset and the moralising of food choices. Several projects are underway at the University of Eastern Finland that seek to help embrace a gentler and more accepting approach to food and eating in food education.

Mari and Sari are going out for lunch. Mari orders a salad and a vegetable smoothie while Sari opts for a hamburger with fries and a large soda.

What kinds of mental imagery do the women’s choices evoke? How do you see Mari? What about Sari? Studies have shown that our attitudes toward food are often inadvertently accompanied by a moral undertone. We judge food choices in terms of a health-obsessed model and think that a person who eats healthy is also good and virtuous, while someone who chooses to eat fast food is somehow inferior and probably has problems with life management. Social norms also easily determine what and how much a woman is allowed to eat before she causes disapproval, for example.

“Certain foods have been stereotyped as healthy or unhealthy. As a result, we often forget the basic idea that a diet happens over the long term and is not dependent on individual choices but can accommodate a variety of foods,” says Sanna Talvia, University Lecturer in Home Economics.

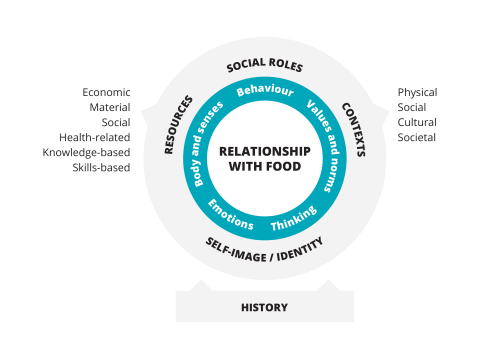

She is one of the researchers in the multidisciplinary research group on food education at the University of Eastern Finland. Projects related to food education are largely based on the concept of a food relationship framework developed by Talvia and Doctor of Psychology Susanna Anglé as a tool to aid in the planning and execution of nutrition education.

“There has been strong and partly justified criticism of traditional nutrition education since the early 2000s, but few actual pedagogical innovations or concrete proposals have been put forward. A new perspective was needed, which is why we set out to develop a new model of food and nutrition education.

At the cusp of a transformation

The first steps in vocational nutrition education in Finland were taken at the end of the 19th century. At that time, the focus was on preventing deficiency diseases and caring for the poor. After the Second World War, the emphasis on nutrition education shifted to the prevention of diseases of affluence.

"These days, we think that in addition to promoting healthy choices, the purpose of food education is also to increase sustainable development and knowledge of food cultures,” says Talvia.

We are at the cusp of a transformation, and there have already been encouraging developments. Nothing changes overnight, but the goal is to develop food education in order to change our relationship with food and eating to a positive one. The goal is also that we learn to appreciate a wide variety of foods and to listen to the messages about eating that our body sends. We should also make sure to eat regular meals.

“Studies have shown that such an approach can have significance to public health by supporting weight management and helping prevent eating disorders," says Leila Karhunen, University Lecturer in Clinical Nutritional Science.

According to her, rethinking food choices and eating behaviour to be more accepting and appreciative can help achieve these goals.

No one way of looking at food

Naturally, the intention is not to discard nutritional recommendations entirely but rather to challenge the way we think about food in terms of black and white and “right” or “wrong” eating. We need to understand that a person’s diet is the sum of many parts based on different aspects of their life.

"In order to define food education, we must first determine what is meant by education and pedagogy. In addition, we need to think about where and how food education takes place and how we perceive our socio-cultural environment, values and norms and material world,” Talvia lists.

For this reason, the aim has been for representation in the research group’s projects to be as multidisciplinary as possible. New disciplines that have been brought on board include psychology and psychotherapy.

A multidisciplinary approach is also beneficial in that it makes it possible to see in concrete terms how many different approaches there are to food education and its concepts. The different perspectives of pedagogical science, psychology, nutrition science, nutrition therapy, food economics, community education and home economics both enrich one another and occasionally clash.

“Sometimes, we notice that we’ve had a long discussion about a concept only to realise that we’re talking about the exact same thing using different terminology. In the end, however, we all share the same goal: promoting all aspects of wellbeing,” says Karhunen.

The intention is not to discard nutritional recommendations entirely but rather to challenge the way we think about food in terms of black and white and “right” or “wrong” eating.

Sanna Talvia

University Lecturer in Home Economics

Shifting focus from weight to wellbeing

One of the aims of food education is to shift from fixating on weight to instead focus on wellbeing. This means that everyone should be accepted as they are, regardless of weight or other external factors.

“This is called a weight-neutral approach, as health can be improved regardless of weight. In this way, the concept of the food relationship framework is also linked to the “healthy at every size” mentality, in which overall wellbeing is more important than a specific body weight. Health is not only physical but also psychological and social,” says Talvia.

All this, however, requires a new way of thinking, both from educators as well as the general public.

“We researchers have also had to dig deep to understand what food education means to us personally. Although we have access to a great deal of scientific data and every nutritional recommendation ever made, particularly as educators, we need to reflect on our own relationship with food.

Even if we know the healthy eating plate and other recommendations perfectly, our own beliefs and personal history always play a part.

“Scientific knowledge works like a mirror against which these beliefs and thoughts can and should be reflected. If they are excessively at odds with scientific information, we need to have the courage to change them. I know that this is difficult as these thoughts are often very deeply ingrained in us,” says Talvia.

Our relationship with food begins in childhood

“I believe in the possibility of growing out of fixed views, but it is of course known that what we learn as children forms a strong foundation on how we see things. For example, emotions and physical experiences we associate with certain foods often stem from childhood.

According to Talvia, a person can, for example, follow nutritional recommendations to the letter but still be anxious and ashamed of their relationship with food.

“That’s why it is not insignificant how we talk to children about food and attitudes toward it. One of our sub-projects has to do with introducing food education as part of early childhood education and care.

When researching schools and curricula, it has become clear that nutrition education at schools can still be guided by strong attitudes of how obesity is something that is reprehensible and needs to be fixed.

“Under this approach, it easily follows that only a certain type of body is seen as right, with other considered immoral. Or that healthy eating is seen narrow-mindedly as an individual, rational and virtuous choice.

However, the truth is that food-related choices are the sum of many parts. They involve interpersonal and social factors that make it easier or more difficult to eat healthy. For example, our society and community influence whether healthy food is readily available, how much it costs and whether everyone can afford it.

“We are also strongly influenced by our genes. Our genetic sense of taste is inherited in the same way as temperament. For example, if we are anxious about new things in life in general, this is often reflected in our relationship with food as an unwillingness to explore new tastes,” says Talvia.

We also talk about “supertasters” who can taste the bitterness in vegetables more readily than others, for example, and are sceptical about certain foods as a result. Others, in turn, approach everything new, including food, with passion, curiosity and an open mind.

“That’s why individual choices related to food should never be used to make comparisons between individuals. Our starting points are often so different that our food habits should also be viewed from the perspective of this diversity of backgrounds. One of the basic principles in food education is that we do not make value judgements on people based on their diet or weight but want to support individual wellbeing through food education,” Karhunen sums up.

Understanding food-related phenomena

Different religions have their own moral rules about food. It is argued that in recent decades, traditional religions have been replaced by a more secular “religion of health”. It preaches that a good person is someone who eats and lives healthily.

“In other words, dividing foods into right and wrong is by no means a new phenomenon, and I don’t believe we will ever be rid of it entirely,” says Talvia.

Consequently, professionals would do well to understand different food-related phenomena. Moral emotions associated with food and the idea that “I’ll be accepted once I eat right” should be discussed as they may prevent us from making food choices based on our wellbeing.

“In food education, it is helpful to recognise the complexity of food. This way, educators and teachers can have a better understanding of why people sometimes make odd choices when it comes to food.”

It is also essential that educators come to terms with their own relationship with food. At best, this can be a professional asset that helps the educator be more humane and understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of people.

Karhunen says that accepting and appreciating imperfection is important, both in one’s own relationship with food and in those of customers.

“We have tried to highlight this aspect in recent years on food education in nutrition science, early childhood education and home economics. We have received positive feedback on the concept that people can explore their relationship with food already during their studies,” she sums up.

It is essential that educators come to terms with their own relationship with food.

Leila Karhunen

University Lecturer in Clinical Nutritional Science

Gentle acceptance, not judgment

Our relationship with food is a topic that is very intimate and personal. Eating is necessary for survival, and it involves many emotions that tie into our identity and self-image. For this reason, how we perceive food is not insignificant.

“Even a well-meaning food educator can end up judging people based on their food choices , causing unintended harm . Consequently, the content and manner of interactions are the keys to efforts to support eating habits that promote health and wellbeing.

Both Talvia and Karhunen agree that the most important part of food education is ultimately not the information being passed on but what thoughts are evoked in people by food-related interactions.

“The key is that we look at our own eating in an honest but compassionate way, increasing our awareness as a result. At best, it allows us to break free from the compulsion to change ourselves and put our trust in the power of acceptance.”

A person thus liberated from feelings of coercion and guilt is free to change on their own terms.

“All people are imperfect, including how we eat and view food. That is why we want to emphasise being gentle and kind to yourself instead of self-judgment.”